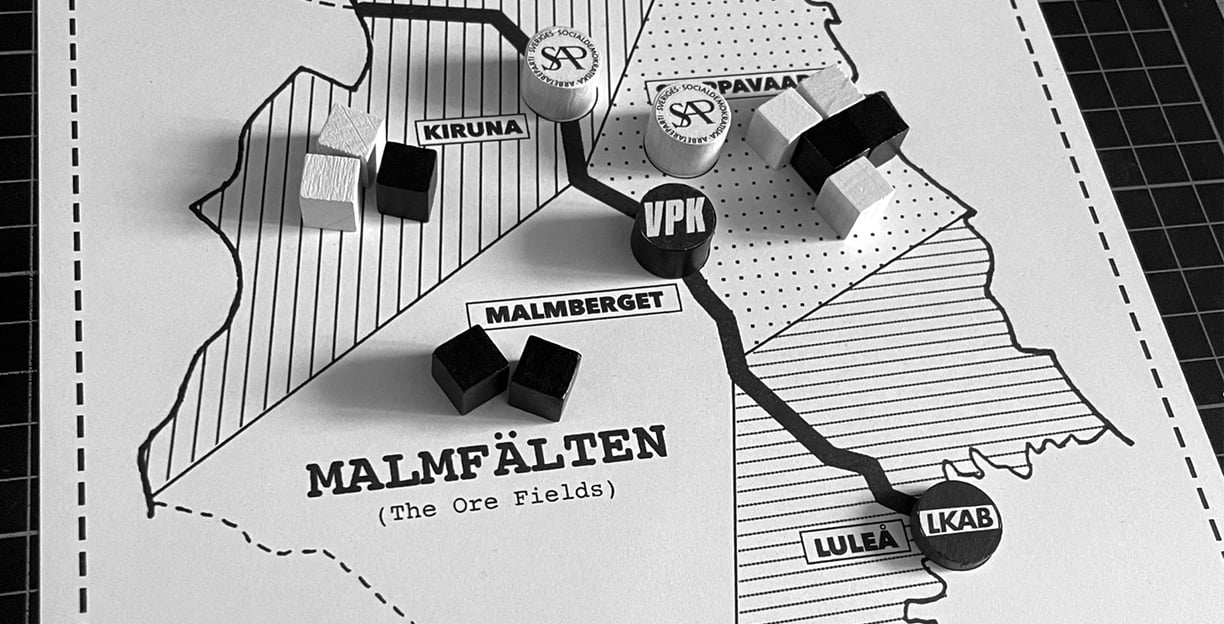

Vi är ej maskiner (We Are Not Machines) is a fast-paced, knife-fight-in-a-phone-booth-type game about the great miner’s strike at the ore fields (Malmfälten) of Norrbotten, Sweden, 1969-1970. Over the course the game, players engage in a political power struggle to organize and manage the massive wildcat strike that broke out on December 9, 1969, when about 4800 miners at Loussavaara-Kiirunavaara Aktiebolag’s (LKAB) mines in Kiruna, Svappavaara and Malmberget, supported by dockworkers at LKAB’s shipping ports, Narvik and Luleå, halted work for 57 days.

Vi är ej Maskiner

GAMEPLAY

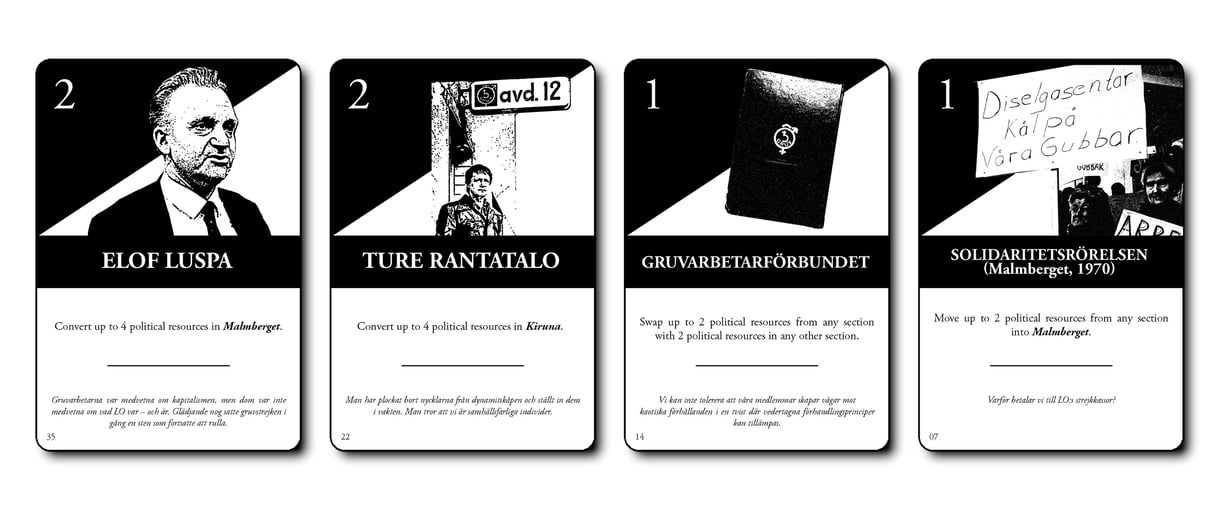

This game seeks to capture the tensions in collective efforts to organize extra-parliamentary action against capital. Players are, in principle, on the same side and take on the roles of the strikers, internally split between social democrats, unionists and communists, in an effort to build and maintain a united front against LKAB (the company/management) and the state. As such, players are part of the central committee leading the strike, at once allies and rivals: on the one side, players must cooperate to prevent LKAB from breaking the strike by exploiting their own internal conflicts, diverging interests and disunity; on the other side, players must use their cunning to individually pursue their own ideological agendas in order to win the game.

Historically, during the great wildcat strike in 1969, the social democrats and unionists advanced a policy to solve the conflict smoothly in line with the policies of the union, The Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO). The communists, on the contrary, were instead working to sustain the strike by rejecting the unions in order to promote principles of direct democracy and syndicalism. This well-worn historical conflict between social democrats, unionists and communists is at the heart of this game; their ideological home bases represented in the communist den, Malmberget, and the social democratic nest, Kiruna. Yet, players are neither docial democrats nor unionists or communists; they are all, and they must bicker, negotiate, coordinate and carefully organize their political resources to form a united front against their oppressors. But they must do so without stirring up too much internal conflict to be exploited by the company.

HISTORICAL NOTES

The wildcat strike in Norrbotten in 1969-1970 exposed the cracks and fissures in the social democratic welfare project and reflected a crisis of confidence within the trade union movement. However, the organizational complications and contradictions within the central strike committee itself also became arenas for ideological conflicts between social democrats, communists, unionists and non-aligned members. When the wildcat strike erupted in December 1969, the social democratic majority of the union federal board based in Grängesberg considered congressional motions from non-party-affiliated members in the departments of Norrbotten as communist. To the federal board, the miners in Norrbotten leading the strike violated the collective agreement that the Gruvindustriarbetareförbundet (Gruv) had signed with LKAB.

While the union had historically been responsible for negotiating the price of labor, i.e., the salaries of the workers, the miners, on the contrary, wanted this entire constellation brought up for negotiation itself. To this end, the miners of the central committee demanded that negotiations on their part be conducted locally and transparently through the principles of direct democracy. As the wildcat strike broke out, this was soon institutionalized when miners at the departments in Kiruna (Avd. 12), Malmberget (Avd. 4) and Svappavaara (Avd. 135), established a central strike committee composed of 21 elected members in charge of implementing decisions. Those initially elected were people, who had previously held positions of trust within Gruv, including social democrats and communists.

On 29 December, 1969, the central committee made a proposal to form a new delegation of 27 members, thereby expanding the committee with two delegates from each department: Avd. 12 and Avd. 4, and two union officials. The central committee now included union representatives, who had so far worked against the strike. As the former social democrat and purported communist Elof Luspa, who were himself part of the committee, noted:

“I think the 21-man committee was very good, until we took in the six union representatives. We should never have done that. It was they who crushed the strike. Slowly, but surely.” [Jag tycker att 21-mannakommittén var väldigt bra, ända tills vi tog in dom sex fackföreningsrepresentanterna. Det skulle vi aldrig ha gjort. Det var dom som malde sönder strejken. Sakta, men säkert.]

The expansion of the central committee marked a turning point for the strike. In addition to the parties, the social democratic party (SAP) and the communist party (VPK), who were demanding loyalty from their members to keep them in line, the union representatives (Gruv) actively began to fracture the unity of the delegation from within. This was in turn exploited by news media covering the strike, effectively undermining public support for the miners, as well as LKAB taking the opportunity to further divide the committee. These are the events this game seeks to simulate.

DESIGNER'S NOTES

I sometimes feel like I was born in the wrong century: born too late to be part of the struggle between labor and capital; born too soon to be a teenage star influencer on social media; born just in time to experience the final stages of planetary collapse under late capitalism. The 20th century, unlike our contemporary moment, was, at least ideally, characterized by a notion of revolution. Or rather different notions of a revolutionary process. Ideas about social progress in the past century furnished the base for political struggles over the organization of society: liberal and conservative forces fought to structure this development in ways that did not challenge political and economic power in any significant way, while socialists, communists and anarchists scrambled to accelerate or fracture the forces of capital to accomplish a completely different distribution of society’s goods.

Whether a revolution was viable during the latter half of the 20th century, politically and economically, following the dismantling of the Bretton-Woods system in the beginning of the 1970s and the neoliberal counter-revolution of the 1980s, revolution was nonetheless a very real potentiality animating the collective registers of feeling and situational awareness among people growing up in the years after World War 2.

Today, notions of social progress, revolution and class struggle have been replaced by the cursory nomenclature of culture wars, trivial influencer activism and blunt awareness campaigns. No regular, middle-class wage slave, nor any lifestyle-politician or head of government in the global north truly believes in revolution beyond the market. Nor do they consider any notion of social progress beyond the technological inventions of new apps, synthetic food, anti-obesity prescription drugs, decarbonized electric cars, solar panels and vertical farming. The Western world wants commodities at the expense of life, order before justice.

Unlike the way the idea of revolution has animated fantasies about other ways of organizing collective life, our contemporary moment is framed by a new delirious hyperpolitical ambience. The emergence of far-right christofascism, accelerating ecological collapse and new modes of algorithmic management harnessed by capital for profit, not for living bodies, life and the biosphere, constitute the social force fields we live in. If anything, our current affective posture and visions of the future are propelled by what Laurent Berlant calls “cruel optimism”: what we desire, or rather what we are commanded to desire, and what we tend to say is valuable to us, are obstacles to our flourishing as living beings. The logics of capitalism are in a very real, material sense debilitating living bodies, human and nonhuman. Indeed, it is damaging to life itself, while we fight for our right to be exploited as if it were rebellion.

How is this real-world predicament of imminent ecological collapse in times of institutional gridlock and late capitalist christofascism related to this game?

There is a generational answer to this: to somehow simulate the political struggles of the 20th century for generations born at the end of history, like myself, the millennials, the zoomers, the alphas and the betas. Those of us, who live in the lethal debris of the neoliberal counterrevolution of the 1980s, doomed to generational warfare and identity politics because we live in a false classless society. Growing up in the hyper-consumerist, post-democratic void of the 1990s, we lack suitable equipment to combat those forces that are currently mauling all life on earth: without the categories and the institutional fortresses of the previous generations our ability to construct maps of our social existence within the larger capitalist cosmology of which we are part subsides. Indeed, without the organizations and categories once weaponized to treat the problem of capitalism and inequality on its distinct, class-based terms, we are practically and rhetorically powerless. The irony being that the lifestyle politics of our time affords a sociology for a world that has become less sociological. This game is my personal, yet feeble bid to reinvigorate a lost timespan of political struggles that are still highly relevant today.

Our increasing inability to envision worlds beyond the capitalist horizon, as well as our failure to recognize the social relations and power structures that shape our everyday lives for the worse, create a sense of political impotence, apathy and cynicism. Worse: it hypernormalizes what Mark Fisher terms “reflexive impotence”: we know things are bad, but more than that, we know that we cannot do anything about it. This game is an infirm attempt to look beyond, or rather look back upon the capitalist horizon, and revive the perpetual political struggles of old that have been varnished by neoliberal ideological blackmailing. In part for the purpose of telling stories interactively from the side of labor rather than capital. And in part to convey a fraction of Scandinavian economic history, which is predominantly marginalized in board gaming.

The concept of revolution, and its adherent categories of class struggle and economic war, outlined horizon of political action in the 20th century. Without the idea of revolution, strikes, riots, national liberation struggles, but also the labor movement’s reformist choreographies with capital, by which compromises were made with the ruling classes, would have made no sense at all. Nowadays, what seems to be forgotten in our crisis of democracy and collective amnesia in the West is that the threat of revolution forced the ruling classes to extend political rights to larger sections of the population. Class war pushed the bourgeoisie to consider wages as an investment rather than a cost, making real material changes to the living conditions of ordinary, working people.

As the revolts in the latter half of the 20th century were crushed, from Paris 1968 to Bologna 1977, the notion of revolution collapsed with them. In our current hyperpolitical moment of too late capitalism, that contradictory moment of instant gratification and immediacy where overmuchness of lateness arrests itself, where the future is eclipsed and the present immanentized on zero-hour contracts and digital media, revolution, insofar it does not pertain to the way the next smartphone “revolutionizes” telecommunication, is a dangerous emotion. A terrorist logic. But, as Hannah Arendt writes, herself in no way revolutionary, it is difficult to think, or even fight for, freedom without a notion of revolution. Yet, the problem being today that we do not even know what freedom is.

/ Jannik Friberg